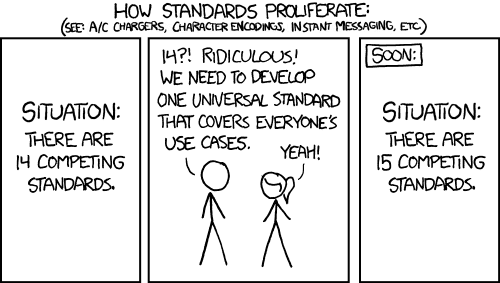

The xkcd comic above illustrates the difficulties of creating a universal standard, and why it often creates yet another competing standard instead. This broadly applicable lesson explains the wide array of open source operating systems available today.

One of the most common experiences that someone exploring alternative operating systems on their own may encounter is feeling overwhelmed by the sheer amount of choice available. While I have no real solution for this feeling, I hope that my own “best of kind” list can be useful regardless.

Before my recommendations, here are some resources that I find helpful:

Many options exist in this space, but a great all-around pick that I always fall back to is Linux Mint. The Cinnamon edition stands out in particular, as it feels user friendly and polished, yet it also empowers the user. The large, helpful community provides exactly what someone new to Linux will appreciate. I feel confident pointing to Linux Mint for this use case, as it showcases the unique strengths of Linux in an approachable way to new users.

Red Hat, the largest Linux company in the world, backs Fedora. It offers many compelling features out of the box, such as the SELinux (Security-Enhanced Linux) mandatory access control system and the copy-on-write filesystem known as btrfs. If taking advantage of new Linux features and keeping a finger on its pulse matters to you, Fedora is a sensible choice.

Qubes OS focuses on security as an operating system designed to separate different aspects of your digital life into virtual machines, also called qubes. The idea is to compartmentalize everything so that if one qube gets compromised, the rest of the system remains unaffected. Qubes OS integrates Whonix which is a huge privacy gain. I highly recommend it to anyone that prioritizes the security of their machine over all else.

Arch often serves as the first advanced Linux distribution that people try. A distribution you install from the command-line, Arch aims to provide the newest releases of software in its repositories. The Arch wiki provides an excellent source of information, and a massive selection of software is available through the Arch User Repository (AUR). Arch offers a middle ground between customization and practicality that many people appreciate.

Gentoo prioritizes extensive customization and choice. Portage (Gentoo’s package management system) exposes a wealth of options to the user, allowing them to adjust the compile time options of software they install through something called “USE flags.” Additionally, you choose components like the system logger and init system during the installation process, which also takes place at the command-line. Gentoo’s wiki and its knowledgeable yet friendly community make it one of the best ways to learn about the deep inner workings of Linux.

Void falls somewhere between Arch and Gentoo in my eyes. It feels more Unix-like than Arch, yet it doesn’t lean as heavily into customization as Gentoo. Void’s package manager (xbps), init system (runit), and alternative C library support (musl) serve as major selling points of the distribution. I can see the logic behind many of the decisions and design choices that the project makes. For example, I think mandoc provides an excellent manual page system, and Void uses it by default.

OpenBSD is a Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) system that has a strong focus on security, portability, simplicity, and correctness. OpenBSD features some of the best documentation of any project I’ve used, and it introduced me to a lot of software that I still admire to this day. For me, it remains unmatched on the server side due to OpenBSD’s simplicity and secure by default approach. Development moves in a more deliberate, controlled manner compared to Linux, which moves rapidly and more chaotically. Here are some more of my thoughts on OpenBSD.

GrapheneOS is a version of the Android operating system that focuses on privacy and security. It’s specifically designed for Google Pixel devices due to the merits of that hardware. GrapheneOS delivers unique advantages including sandboxed Google Play services, extensive system hardening, and secure replacement applications. For mobile operating systems, I know of nothing more secure.

NixOS presents a different method of system management: describing your desired system in a configuration file and then issuing a single command to build it. This approach offers definite advantages and I’ve written more about NixOS here.